Maximilian Popp / Der Spiegel

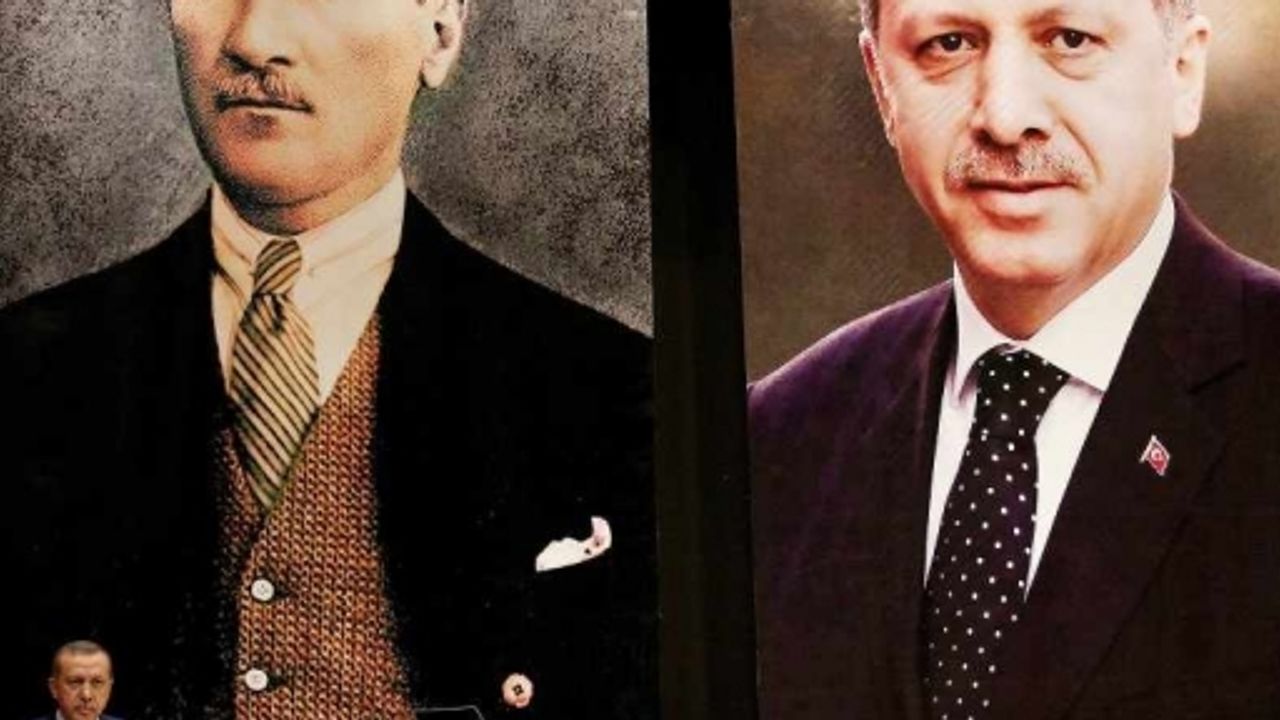

Istanbul public prosecutor Zekeriya Öz has investigated Turkey's elite, those who were seen as untouchable: politicians, journalists, attorneys and generals. Öz has been the most important criminal prosecutor under Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan, helping him take legal measures against the network known as the "Ergenekon," whose members were allegedly planning a coup against the government. But only a few months after the end of the five-year trial, Öz has now turned against his former sponsor.

.jpg)

Shortly before Christmas, police arrested more than 50 suspects, including politicians with the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP), influential businesspeople, and the sons of three cabinet ministers. The investigations were initiated by Öz, who was subsequently taken off the case. The scandal has taken Erdogan into the most serious crisis of his nearly 11 years in office. The corruption scandal within his inner circle is jeopardizing the power of the AKP and threatens to tear it apart -- and that in an election year, in which Erdogan apparently wants to be elected president.

The ministers of economics, the interior and urban development resigned on Dec. 25, after the arrest of their sons, who allegedly accepted bribes for providing building permits and public contracts. The next day, Erdogan fired seven other ministers, filling their posts with his confidants.

Several senior lawmakers, as well as the head of the state-owned Halkbank, who allegedly orchestrated oil deals with Iran, were also arrested. They are accused of circumventing sanctions against Tehran that prohibit monetary transactions with Iranian banks by paying several billion euros worth of gold in return for oil. When the police raided the bank head's home, they found $4.5 million (€3.3 million) in shoeboxes. But this is probably only the beginning of greater turmoil. EvenErdogan himself is becoming increasingly caught up in the corruption scandal. The urban development minister who had resigned, Erdogan Bayraktar, has called upon the prime minister to step down as well. Bayraktar claimed that he had approved the construction projects in question at Erdogan's instruction.

Further Arrests in the Pipeline

Investigators are apparently planning further arrests, with a list of suspects that includes Erdogan's son Bilal. The 32-year-old is the founder and a board member of the influential Türgev Foundation, which acquired a government property in Istanbul's Fatih district at a very favorable price, allegedly paying about €3 million in bribes in return.

A summons for Bilal Erdogan, signed by Istanbul public prosecutor Muammer Akkas, has since been published. But police officers refused to arrest either him or a number of AKP lawmakers, probably on instructions from the political arena. Akka was also removed from the case. In a statement last Thursday, he said: "My investigations were blocked. The judiciary was apparently put under pressure."

Meanwhile, Erdogan is trying to paint the scandal as a conspiracy against his government. He blames it on a "gang" that aims to harm Turkey . In a televised address on Jan. 1, Erdogan called on his fellow Turks to help fight what he called a plot by foreign-backed elements. "I invite every one of our 76 million people to stand up for themselves, to defend democracy and to be as one against these ugly attacks on our country," he said. But even Erdogan's supporters are irritated by his tirades. And the louder he gets, the clearer it becomes that the once popular premier is fighting for his political future.

Erdogan, a former mayor of Istanbul, came into office on the promise of putting an end to the cronyism of his predecessors. It helped get him elected in 2002 and has seen his government returned to office two times since then. But the AKP is not governing as cleanly as Erdogan claimed. It has long been plagued by allegations of corruption. In the embassy cables published by WikiLeaks in 2010, US diplomats reported "corruption at all levels" in Turkey.

'No One Wanted to Listen'

"We have addressed the subject of corruption within the government for years, but no one wanted to listen," says Aye Danisoglu, a member of parliament for the opposition party, the CHP. "It finally took a dispute within the Islamic camp to uncover the dirt of the past few years."

The accusations have never been this detailed, nor have they been this dangerous for the prime minister. For the first time, it is not only members of the opposition who are attacking Erdogan, but also some of his previous supporters, especially those aligned with the Turkish preacher Fethullah Gülen.

Gülen lives in exile in the United States. His supporters have established schools, media companies, hospitals and companies worldwide. The Gülen community seeks to portray itself as a civil society movement that primarily promotes education. But former members describe the community as hierarchical, political and Islamist.

Gülen and Erdogan long enjoyed a successful cooperative relationship. Gülen secured votes for the premier, while Erdogan protected the community's business dealings. With Erdogan's patronage, Gülen supporters secured key positions with the police and in the judiciary. In the Ergenekon trial, Gülen and Erdogan collaborated to bring down their chief adversaries: the military and the secular opposition.

A 'Declaration of War'

Zekeriya Öz, considered a Gülen supporter, was the chief prosecutor in the trial, the largest in recent Turkish history. The accused allegedly planned terrorist attacks to overthrow the government. Observers criticized the trial, which ended in August 2013 after five years, calling it a farce. Details from the trial were regularly leaked to media organizations owned by the Gülen movement, and regime critics were publicly denounced.

In recent months, however, the alliance has begun to crumble. Gülen's supporters had apparently become too powerful for Erdogan. At the same time, he obviously came to perceive them as disloyal, dismissing a number of officials aligned with the community. Gülen supporters in the judiciary subsequently attempted to prosecute the intelligence chief, an important confidant of the prime minister, but were unsuccessful. In November, Erdogan announced that Gülen tutoring centers were to be shut down. The educational facilities prepare pupils for university entrance examinations and are an important source of income for the movement. The newspaper Hürriyet called the move a "declaration of war."

For this reason, the investigations can arguably also be seen as the Gülen movement's attempt to exact revenge on the prime minister. Erdogan calls it a "very dirty operation" and accuses Gülen supporters of trying to establish a "state within the state." Gülen replied with a video address, in which he said: "May God bring fire onto the houses of those who do not see the thief, but instead persecute those who are hunting the thief."

This is the second time that Erdogan has come under fire recently. In the summer, more than three million people protested for months against the redevelopment of Gezi Park in Istanbul. But the movement soon expanded into a broader protest against Erdogan's increasingly despotic style of government.

After almost 11 years in office, Erdogan seems increasingly autocratic and disconnected from reality. He has now replaced many capable advisers with loyal yes-men. Success makes some politicians more relaxed, but in recent years Erdogan has, in many respects, developed into precisely the type of autocratic ruler he once vowed to abolish. Critics have been locked away under Erdogan's rule. Turkey has more journalists and supposed terror suspects in prison than anywhere else.

AKP at Risk

Erdogan reacted obstinately to the protests in the summer, berating his critics as "bums" and having his security forces fire tear gas at them. He has also proved to be relentless in the current crisis. Some 500 police officers have been transferred, and Erdogan also attempted, albeit unsuccessfully, to gain control over investigations by decree. But in contrast to the Gezi protests, this time Erdogan will not be able to bring the crisis under control by taking a tough approach. It is already becoming clear that the scandal could break apart his party.

Erdogan's goal of having himself elected president in the summer is becoming more and more tenuous. He would like to endow the position with significantly more power, but he is now unlikely to secure the necessary two-thirds majority in parliament. But under Turkey's Political Parties Law, he can no longer run for prime minister. It's possible that he will try to rewrite the law to remain in power, but there is already growing resistance within the AKP to such a move. President Abdullah Gül, in particular, now opposes his longtime ally.

Finally, the economy, the most important factor in persuading many citizens to vote for Erdogan, is growing weaker. The Turkish lira recently fell to a record low. Foreign investment, which brought in capital that fueled the boom of recent years, has been in decline for some time. If investors continue to withdraw money from Turkey, the result could be an economic slump, which could cost Erdogan votes.

The opposition is sending a candidate with serious prospects of winning the race for mayor of Istanbul in next March's local elections. This makes AKP officials increasingly nervous, because they know that whoever loses Istanbul will lose Turkey.